Industry 4.0

Designing the Future:

How Autodesk is Using Generative Design

Advances in industry 4.0 technologies such as additive manufacturing and artificial intelligence are continuing to drive a transformation in how products are developed. Ellen Daniel hears from Autodesk iconic projects lead Paul Sohi to find out how technology is changing the game

There is no doubt that the world of manufacturing and design has been transformed over the past decade, with the technological advances of industry 4.0 changing the way in which products are conceptualised, produced and delivered to consumers.

With the tagline "make anything", California-based software corporation Autodesk "makes software for people who make things", spanning industries such as architecture, engineering, construction, manufacturing, media, education and entertainment.

Autodesk is well known for its computer aided design and digital prototyping software, putting it at forefront of design technology.

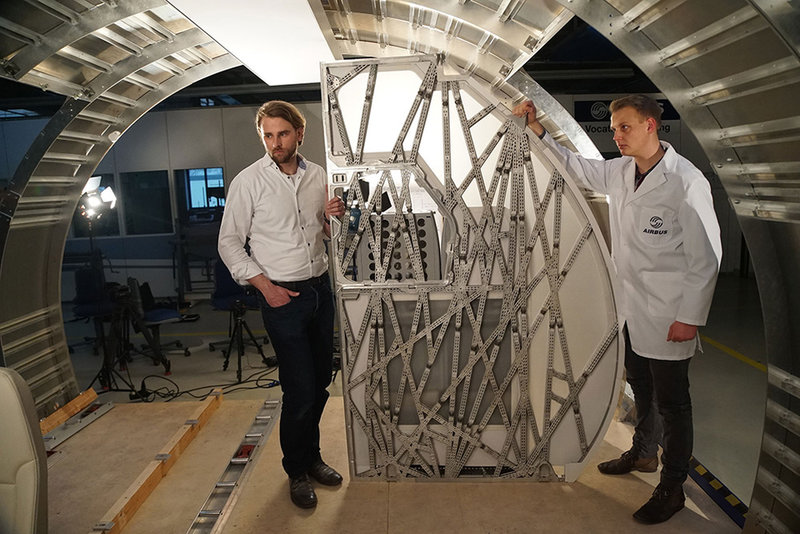

Airbus workers test the placement of a bionic partition developed using Autodesk generative design. Image courtesy of Autodesk

Autodesk: Bringing design ideas to life

Fusion 360 is Autodesk's computer-aided design, manufacturing and engineering software platform, which allows users to design products, create simulations for how they may work in the real world and translate designs into 3D prototypes.

With a background in architecture, Paul Sohi is the iconic projects lead and Fusion360 evangelist at Autodesk.

"I studied architecture at university and practiced as an architect for a short period of time before realising that my career was probably going to be mostly drawing toilets!” says Sohi.

“Probably my favourite thing about the job is getting to meet people who are like: ‘I have this really crazy idea’ and I get to say to them: ‘tell me more’.”

“That's not what I wanted to do. So I transitioned into industrial design. I was running my own business practice, and that's how we first got connected to Autodesk. And as things evolved, I decided to close the company down and join Autodesk on the Fusion 360 evangelism team.”

Sohi now works with companies in manufacturing and design, connecting those innovating in the design sphere with tools that could help them do.

“My role at Autodesk for the last five years has been primarily focused on developing partnerships with companies who are doing really interesting manufacturing and design challenges and helping them deliver on those challenges,” he explains.

“Probably my favourite thing about the job is getting to meet people who are like: ‘I have this really crazy idea’ and I get to say to them: ‘tell me more’.”

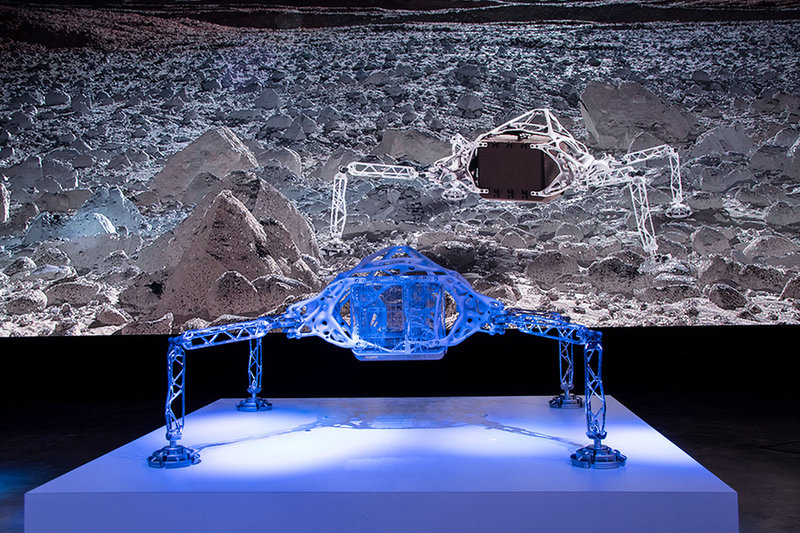

An interplanetary lander designed in collaboration between Autodesk and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Image courtesy of Autodesk

Crazy ideas through generative design

Many of these “crazy ideas” are realised through a key pillar of Autodesk's work: generative design. This technique allows different design options to be explored using artificial intelligence (AI). Users enter parameters or criteria the design has to meet, and then AI generates potential solutions that human designers may not have necessarily come up with.

“In today's day and age, designers, manufacturers, engineers are all under immense pressure to deliver better products faster and for less money,” says Sohi.

“There's only so much that a human being can do on their own. What generative design enables a person to do is answer a bunch of questions around specific problems in whatever product they're working on up front and use that information to expedite the process.”

Autodesk's generative design unit is certainly not short of unorthodox applications, with a back catalogue of varied and unusual projects.

Last year, the company partnered with Volkswagen to reimagine the iconic VW Bus using cutting-edge design technology. Harnessing generative design, the bus's wheels, wing mirrors and steering wheel were modelled in a way that maximises durability while minimising weight.

“With Volkswagen, the process of designing alloy wheels for any vehicle can be as long as two years. Which obviously is too long now, especially with the pace that things are moving,” he explains.

“There's only so much that a human being can do on their own.”

“And with electric vehicles getting better and better, we can't rely on that old process. What generative design enabled them to do is input all of their engineering requirements upfront and have it output hundreds, if not thousands of different viable and manufacturable design solutions based on the criteria they set."

In 2017, Autodesk also partnered with paralympic cyclist Denise Schindler to create the first fully additively manufactured prosthetic, which Schindler wore at the 2016 Rio Paralympics.

Sohi has also been involved in a project that used 3D-printed titanium and aluminum in the manufacturing of skateboard parts, in collaboration with 3D printing service company Shapeways.

Autodesk’s other partnerships include a project with Airbus to both develop a bionic partition for its planes and reimagine its engine assembly factory layout using generative design; a collaboration with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to develop an interplanetary lander and an initiative with architect and designer Philippe Starck and furniture maker Kartell to produce the world’s first production chair co-designed by AI.

When it comes to collaborating on such projects, Sohi explains that inspiration can come from a variety of sources.

“Usually a company has seen something that we've done in the past, and thought it was really cool, and they wanted to do some kind of collaboration with us and they'll reach out. And if it's the other way around, it's usually me reaching out to a company that I personally really love and think they do really awesome things,” he says.

“And we [would] just really love to work with them. And so I go to them and will be like: ‘hey, I love what you guys do. How would you feel, you know, working on X with me?’ And when you tell them it's free, no-one ever says no!”

AI Chair, the world’s first production chair imagined by a human and co-designed with artificial intelligence. A collaboration between Philippe Starck, Kartell and Autodesk. Image courtesy of Autodesk

Additive manufacturing: The “new normal”

Generative design goes hand-in-hand with additive manufacturing technology.

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, has been available since the 1980s, when researchers in Japan developed a way of building objects out of layers of photopolymers.

However, although well known to those both within and outside the world of design and manufacturing, the technology was initially slow to live up to the hype surrounding it, with high costs, limited materials and the quality of the final product all creating barriers to its widespread adoption.

This led the technology to be primarily used for prototyping, but thanks to advances in the technology, it is now used in manufacturing across numerous industries, with the 3D printing market now growing at a rate of 12.5% per year according to Deloitte.

Sohi believes that the democratisation of this technology has had a significant impact almost every design and engineering practice.

“The thing that makes me the happiest is if you go back as little as 10 years, additive manufacturing was something that was restricted to companies with massive budgets, or universities using it as an educational tool. And in the last four or five years, additive as a process has been integrated as the new normal into every design and engineering practice I've come in contact with,” he says.

“They don't even think twice about it if they are designing something, they're conceptualising. Additive manufacturing definitely makes a play in that, even if it's just at a prototyping stage.”

“If you go back as little as 10 years, additive manufacturing was something that was restricted to companies with massive budgets.”

He reflects that this shift in approach has happened rapidly.

"I don't think I'm that old – I'm 32 – and when I was at university, the primary method by which we would prototype and demonstrate ideas was physical model making. And that's a laborious process. And that's only going back 12 years,” he says.

“Now what I can do is go from sketch to 3D model really, really quickly, and then print out a prototype overnight to show to customers, show to colleagues and use that to really expedite the process by which we get to the final product.

“We're seeing this out in the real world too. The typical time to market from ‘I have an idea’ to product on the shelf; four or five years ago that would have been about a two-year cycle. Every year, that time has gone down to the point now where you can have an idea and have it manufactured and on the shelves in a six-month cycle instead, which is amazing.”

With hobbyist 3D printers re-purposed to manufacture personal protective equipment for healthcare professionals during the Covid-19 pandemic, companies such as Nagami exploring 3D-printed furniture and BMW aiming to produce 50,000 3D-printed components for its vehicles per year, Sohi believes that the use cases for additive manufacturing will only continue to expand.

“Because additive as a tech was kind of under lockdown with all the different patents that various companies held, no one really got to see it popularised,” he says.

“We're seeing the popularisation in the last decade because those patents have expired, and so many companies have been able to explore more affordable and desktop versions of these previously gigantic industrial machines. So it's just democratised the tech and I think that's definitely helped people be able to ideate and expedite ideas out much faster than they have in the past.”

Volkswagen Group’s re-conceptualised 1962 Microbus. Image courtesy of Volkswagen.

“The thing that's holding people back is their own anxieties”

When it comes to deploying cutting-edge technologies such as generative design or additive manufacturing, Sohi believes that a number of misconceptions still exist, deterring some organisations from reaping the benefits they offer.

“I meet a lot of companies that have anxieties about trying these technologies out, or they think there's a huge barrier of entry . [But the] barriers are so low now and the availability of learning content is so pervasive,” he says.

“For example, generative design as a technology at Autodesk is only just over a year old now. And understandably, with anything that's new tech like that, and the geometries that they see it produce, there's a natural anxiety to assume that this is out of the question for me or there's no way that I can use it at my company.

“But I find that more often than not, the thing that's holding people back is just their own anxieties more than anything else.”

Over the next few years, Sohi believes that additive manufacturing will continue to become more accessible, fuelled by advances in material science.

“I think in the next five years, the big thing there is probably going to be the availability and democratisation of more advanced materials,” he says.

“I think in the next five years, the big thing there is probably going to be the availability and democratisation of more advanced materials.”

“Right now the barrier of entry for getting a 3D printer for plastic or resins is pretty low. And then you juxtapose that against metals, and it's astronomically high. I think the cheapest [metal 3D printer] I've seen is £50,000 pounds and they can be as expensive as half a million. And it's not just the cost of the machine, but then all the associated safety things that you need around that.”

He also sees potential in emerging technologies within the additive manufacturing space.

“The industry that I'm most excited about is in the field of consumer products and industrial manufacturing and machinery, because of the things that I see around material science. I think the new materials and smart materials that groups at MIT, Cambridge and Oxford are working on are going to have significant impacts on how we think about stuff that we use and how we interact with the things that we use.”

Not only will this help streamline the design process, but Sohi believes that it is fast becoming necessary to re-think manufacturing to reflect the growing need to produce more with less.

“As we accelerate with design and engineering and people demand more and we need to build better products, part of that conversation that people generally shy away from is that we also need to do that with less material,” he says.

“As more and more people move into the middle class, the demand for a better life comes with that, and a 'better life' usually means better things. Products like generative design, which enable us – at the very least from an engineering perspective – to achieve that part of giving products the same performance while using less material as part of that process, is going to become more and more relevant.”

Generative design was applied to the wheels of the new VW Microbus to achieve a weight savings of 18%. Image courtesy of Volkswagen.

Cover image courtesy of Autodesk

Back to top